LONG READ

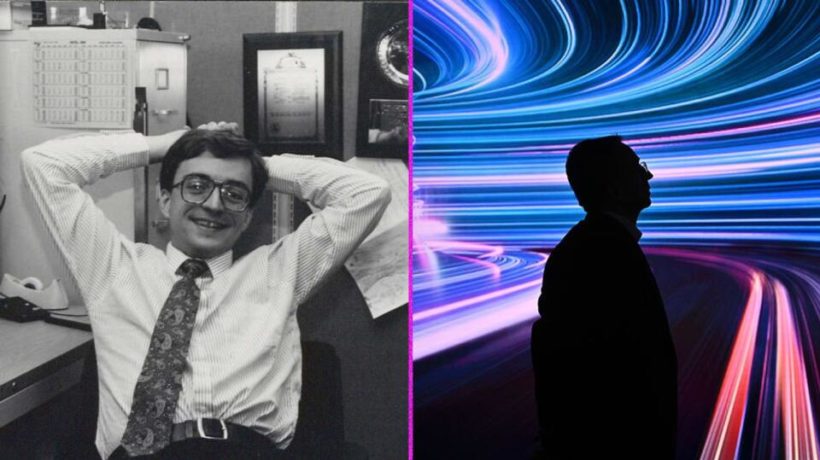

One year ago, Pat Gelsinger gave up his Mac. As Gelsinger explained to me, when Apple adopted Intel’s processors for its computers back in 2005, he “flipped from being a PC guy to a Mac guy,” Now Apple was transitioning away from Intel chips in favoUr of ones it designed itself—and Gelsinger was Intel’s new CEO. Becoming a PC guy again was not a matter of choice.

There was a certain symbolism to his platform switch, but it was just minor fallout from one of several major setbacks that the 54-year-old chipmaker suffered during the tenure of its previous CEO, Bob Swan, who led the company for less than three years. As Gelsinger wrapped up his first week on the job and settled into his home office’s new computing setup, we were chatting via Microsoft Teams in the first of multiple conversations we’d have during his first year as CEO.

For a long time, Intel would have been a leading candidate for any list of the tech companies least likely to run into serious trouble. In 1965, cofounder Gordon Moore gave us Moore’s Law—the prediction that the number of transistors on a chip would double at a rapid cadence, which he later specified as every two years—resulting in ever-greater performance and efficiency. Moore’s Law and Intel went on to be very, very good to each other—and as the computer age bloomed, the world benefited.

In recent years, however, the company’s uncontested preeminence among chip companies has crumbled. Apple’s Intel-free Macs, for example, are by almost any definition its best computers ever. And in 2017, AMD—Intel’s eternal, often bedraggled rival for the business of PC manufacturers—trounced Intel with its first Ryzen processor, aimed at power-hungry users, such as PC gamers. That was the beginning of an AMD renaissance, which continues today.

Most worrisome of all, Intel’s manufacturing capabilities seemed headed in a direction that might put it at a long-term disadvantage compared to . . . well, everybody. In July 2020, it was forced to greatly delay its introduction of chips based on a 7-nanometer manufacturing process, the latest advance in the art and science of packing more transistors into less space. Meanwhile, Intel competitors were readying even more efficient 5nm chips. They’d long ago split up the necessary heavy lifting of silicon progress, with the companies that designed the chips outsourcing production to contract manufacturers in Asia, most notably Taiwan’s TSMC. The success of that bifurcated approach was throwing Intel’s entire business model of designing and producing its own products into question.

Hence, Swan’s departure from Intel and Gelsinger’s arrival—or, to be precise, his return.

Though Gelsinger established his bona fides as a CEO by running virtualization software pioneer VMware for more than eight years, his defining credential is the three decades he spent at Intel in an earlier tour of duty. A protégé of the legendarily competitive Andy Grove—who joined Intel founders Moore and Bob Noyce at the company on the day it was incorporated and became its CEO from 1987 to 1998–he is a walking, talking link to the company’s glory days. Restoring that glory, he says, requires the return of “Groveian principles,” which he describes as involving “deeply technical, blunt, transparent, truthful conversations—pursuing what’s right, being paranoid about the competition, and never assuming it’s right until it’s debated.”

Along with striving to rebuild Intel’s once-fabled culture, Gelsinger has convinced its board to plow at least $43.5 billion—not including any government subsidies or still-emerging plans for Europe—into new chip fabrication plants (in industry parlance, fabs). The company will use some of that capacity to produce semiconductors of its own design. But in a dramatic shift away from the strategy that made Intel a giant in the first place, it also wants to be a major foundry for the entire industry, producing chips designed by others—the same business that made TSMC a behemoth.

Intel’s foundry ambitions aren’t just about creating a major new profit centre for Intel. By bolstering chip production in the U.S., the company intends to play a part in reversing the country’s long decline as a manufacturing superpower. It wants to reduce the chance of future chip shortages like the one currently roiling the global economy. It even hopes to insure against geopolitical disruptions yet to come.

Even Intel watchers who aren’t ready to predict a stunning turnaround see Gelsinger as a smart hire and the moves he’s making as a gutsy, high-potential gambit. “To many people, he is the ultimate Intel CEO at this point,” says Kevin Krewell, a principal analyst at Tirias Research. “Mixing that outside-in and inside-out perspective puts him in a really good position to build the company and move it forward, finally.”

Ultimate Intel CEO or not, Gelsinger has his work cut out for him. Whether he’s succeeded won’t truly be clear until the fabs the company is building are cranking out chips—an eventuality that’s years away. “It’s not like the issues that he’s trying to fix just recently appeared,” says Stacy Rasgon, managing director and senior analyst at Bernstein Research. “They may have just become apparent to most people, but they’ve been building for 10 years. That’s what he’s fighting against.”

That’s pretty much the same assessment of the situation as Gelsinger’s own, though he adds a healthy dose of can-do optimism. Dynamic but unapologetically geeky, human-sounding rather than perfectly polished, prone to emphasizing almost every point he makes with expansive sweeps of both hands, he exudes enthusiasm for the hard work ahead.

“We are going to have some blood, toil, sweat, and tears until we get everything running like it needs to be again,” he told me in June 2021. “No enthusiastic new CEO can come in, and in a hundred days, fix 10 years of mistakes. But we’re well on the way.”

FROM THE FARM TO THE VALLEY

It has been almost 43 years since Patrick Paul Gelsinger, who turns 61 next month, arrived in Silicon Valley. But he is still fond of describing himself as “a Pennsylvania farm boy.” And for all his accomplishments as a technologist and businessperson, he never comes off as living entirely inside the tech-industry bubble.

Gelsinger is a man who’s comfortable beginning his first Intel company meeting as CEO by cheerfully declaring that “Californians are crazy” and disclosing that his wife was initially reluctant to return to the state from the east coast when he was appointed as VMware CEO. The rare tech exec whose faith is part of his public persona, he peppers his Twitter feed with Bible quotes (“‘Make sure that nobody pays back wrong for wrong, but always try to be kind to each other and to everyone else.’–1 Thessalonians 5:15”), as well as the prerequisite Intel cheerleading. He’s also an active philanthropist who climbed Mount Kilimanjaro to raise money for a girls’ school in Kenya and donates half his yearly income to causes, such as Mercy Ships, which sends floating hospitals to developing countries.

Back in his farm-boy days, Gelsinger grew up outside of tiny Robesonia, Pennsylvania: “When you get to nowhere, we’re five more miles,” he jokes. An electronics whiz, he left high school at age 16 by landing a scholarship to a local branch of Lincoln Technical Institute. He was 18–and had never been on an airplane—when Intel recruited him. After relocating to the Bay Area, he started at the company as a quality-control technician while earning degrees in electrical engineering from Santa Clara University and Stanford.

From there, he quickly rose through the ranks. He was the fourth engineer to join the team that designed Intel’s 386 processor, a seminal component released in 1985 as the PC revolution was going into overdrive. For its even more powerful and popular successor, 1989’s 486, he served as chief architect—an accomplishment he still commemorates by pinning a 486 chip to the left lapel of his jacket the way a politician might affix a tiny American flag.

Even early in his career, he exhibited a breadth of interests that would serve him well as he took on more responsibility. “You could talk to him about anything,” says Chuck McManis, who worked alongside Gelsinger when both were young engineers in the 1980s. “He was connected with everybody, from marketing to the circuit-designer guys.”

In 2001, after having taken on several other big jobs, Gelsinger was named Intel’s first chief technology officer. The role could have been a crucial stepping stone toward running the entire company. But when CEO Craig Barrett stepped down in 2005, he was succeeded by another Intel veteran, Paul Otellini. Four years later, Gelsinger left Intel to become president and COO of enterprise storage kingpin EMC.

Today, he says that his departure was not entirely of his own making: “I felt pushed out of the company a bit by Otellini at the time.” But it did result in him becoming CEO—of VMware, which was then part of EMC.

In Gelsinger’s absence, Intel did not exactly flourish. Brian Krzanich succeeded Otellini in 2013 but was abruptly fired in 2018 when Intel learned of a past relationship with a subordinate that violated its anti-fraternization policies. The company then promoted CFO Bob Swan, who’d been at Intel less than three years—its first CEO who was neither an engineer nor a longtime employee.

It was Swan who had the misfortune to be in charge during what The Verge’s Chaim Gartenberg later dubbed “the summer Intel fell behind.” In a rapid-fire sequence of embarrassments, silicon engineering chief Jim Keller abruptly quit after less than two years at the company, Apple announced its plan to switch to its own chips, and Intel disclosed that manufacturing glitches would necessitate the postponement of its plans to ship 7nm processors.

Gelsinger had reportedly been in the running in the CEO searches that resulted in Krzanich and Swan getting the nod; analyst Rob Enderle had even called him, “The one man who could save Intel” in January 2018, five months before Krzanich’s termination. As Intel floundered under Swan, it wasn’t a shocker that he once again looked like CEO material. But Gelsinger says that his conversation with the company began around a far less momentous opportunity: joining Intel’s board.

That was around Thanksgiving of 2020, and at first, it was nothing more than a leisurely exploration of that possibility. “And then, on December 23, the discussion flips,” Gelsinger recounts. “‘Would you be the CEO?’ The tornado was unleashed at that point.”

He was indeed interested—even though he knew the job would make his life at VMware look practically idyllic. The deal was sealed during a Zoom call with Intel’s board on Friday, January 8, 2021, with Gelsinger presenting a strategy memo he’d written and getting the unanimous support he wanted. Over the weekend, he told VMware’s board he was resigning; Intel announced his appointment the following Wednesday.

BUILDING A BIGGER INTEL

Gelsinger’s vision for retooling Intel was simple—but also wildly ambitious. And its urgency was reflected in the fact that he announced the gist of it in a webcast called “Intel Unleashed” only five weeks after his first day as CEO.

Since the beginning, Intel had been an Integrated Device Manufacturer, or IDM—a company that both designed and manufactured its chips. For a long time, that won it bragging rights. But recently, the rest of the semiconductor industry had been deconstructing the task. The A15 Bionic processor in an iPhone 13, for instance, was designed by Apple—using technology from Arm as a raw ingredient—and manufactured by TSMC. Given that the A15 is a 5nm chip designed while Intel was still wrestling with its 7nm transition, divvying up the labour did not seem to be an impediment to progress.

Gelsinger was not about to spin Intel’s manufacturing capacity out as a standalone company, as AMD had done in 2009. His new strategy did, however, involve Intel setting aside its reflexive pride in taking on sole responsibility for bringing a chip into the world. That would include ramping up its ability to serve as a foundry for other chip designers—something the company had only dabbled in previously—as well as being willing to outsource production of its own designs to other chip makers, such as TSMC, when expedient. Intel would also offer up its x86 chip architecture as intellectual property for other companies to tweak for specific purposes—for instance, to fashion a chip highly optimised to run a particular software stack in a huge data centre.

The foundry aspect of this plan would require not just new thinking but also an enormous investment in new chip-production capacity: “We are going to be a big, bad manufacturer at scale,” says Gelsinger. Intel is spending $20 billion on two new fabs at its long-established facility in Chandler, Arizona. It’s sinking another $20 billion into an all-new fab in New Albany, Ohio, the winner of a bake-off between around 40 prospective sites that went on for much of Gelsinger’s first year. Its New Mexico site will get a new $3.5 billion chip-packaging plant. The company also intends to expand its manufacturing capacity in Europe, exact location TBD. And this month it paid $5.4 billion to acquire Israel-based Tower Semiconductor, a foundry focused on specialty chips outside Intel’s traditional wheelhouse.

$20 billion here, $20 billion there—add it up, and pretty soon, you’re talking real money. In fact, Intel is making the largest private-sector investments ever in both Arizona and Ohio. But the company may end up being able to spend billions more on this expansion. In an odd moment of synchronicity between its corporate goals and world affairs, Gelsinger was formulating his plans at the same time that a global semiconductor shortage was leading governments to conclude that assuring a steady supply of chips was too vital a matter to leave entirely in the hands of the private sector.

This shortage was less a single crisis than a perfect storm involving high demand for PCs during the pandemic, Bitcoin tycoons hogging powerful graphics cards to mine cryptocurrency, and a Chinese firm hoarding that country’s chips in the wake of the Trump-era trade war. Even severe weather events and factory fires played a part. The effects rippled across industries: One estimate says that the auto industry alone lost $210 billion in revenue in 2021 due to cars it couldn’t ship because it couldn’t obtain the necessary chips.

Such repercussions weren’t just sobering evidence of how dependent modern living is on computer technology. They were also a reminder of how little the U.S. could do about the crisis, since the country was largely dependent on chips manufactured in Asia. The biggest percentage came from Taiwan—which, given growing fears that China might use force to exert control over what it sees as a breakaway province, made the shortage look like a national security issue.

That the U.S. was a fallen giant of the chip industry was not exactly breaking news: In an oft-cited stat, America’s percentage of semiconductor manufacturing, which stood at 37% in 1990, was just 12% in 2020. By the summer of that year, however, legislators in the U.S. Senate and House were finally ready to do something about it. In Washington’s tortured-acronym tradition, they called their proposed law the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act—better known as the CHIPS for America Act. It proposed to offer $52 billion in incentives to ramp up semiconductor production in the U.S.

Once the U.S. government became interested in spending money to bolster domestic chip production, it was inevitable that Intel would come into the picture. “There’s only three companies in the world that can make capital investments at this scale and have the technology to fulfill it,” says Gelsinger. “It’s TSMC, Samsung, and Intel. It’s that simple. And only one of those is a western company.” As much of its own money as Intel was committing to its current expansion, it would happily accept more in order to move even faster.

Any company that seeks government subsidies risks being accused of mooching for a handout. In this case, Intel contends, it’s merely asking for the kind of support that helped other countries’ chip-producing-capabilities boom as those in the U.S. withered. “Intel is not just competing with TSMC or Samsung,” says Bruce Andrews, a former SoftBank executive and U.S. Department of Commerce deputy secretary who joined Intel in August 2021 as chief government affairs officer. “We’re really competing with Korea Inc. and Taiwan Inc. and China Inc.”

Gelsinger threw himself into the effort to turn CHIPS for America into law, from writing op-ed pieces on the topic to personally lobbying Congress: “I’m getting calls from Senator Schumer on a Friday night, asking for my help getting 10 Republicans to vote positively,” he told me in early June 2021. (That was when he wasn’t making a similar case in Europe, where legislators were alarmed about the chip shortage for the same reasons Americans were and discussing their own subsidies.) On June 8, the Senate passed the bill, and Gelsinger’s efforts turned to encouraging the House to do the same with its version.

CULTURE, PAST AND PRESENT

“We had a product process sync meeting that I jumped into and was participating in, and I was upset with this one little aspect of the update. And it was wonderful, because one of the senior technical guys came back at me and he says, ‘No, Pat, you’re wrong, because of this, this, this, this, and this . . . .’ And he was right, and I was wrong. I still don’t like his answer, but the person who had the data took the CEO to task, and he felt a little bit proud that this is his first time he’s argued with the CEO, and he won.”

Pat Gelsinger is speaking from his home office, bedecked with Intel memorabilia—in one of 37 brief Friday video messages for Intel’s 121,000 employees that he will have recorded and posted by early February 2022. Once again, he is extolling the forthright, egalitarian, and data-driven principles that Andy Grove made famous in his 1996-edition best-seller Only the Paranoid Survive.

Gelsinger does not maintain that this culture requires no updating for 2022 and beyond. Quite the contrary: During his first company meeting video, he told Intel staffers, “It wasn’t a particularly diverse or inclusive culture—it also was combative where it didn’t need to be.” (In his book, Grove himself wrote about bruising management techniques, such as “constructive confrontation,” which he defined as “ferociously arguing with each other while remaining friends.”)

That Gelsinger is passionate about the mindset that once made Intel great while simultaneously acknowledging its 21st-century downsides indicates the complexity of what he’s trying to pull off. For him, Intel’s original culture isn’t the stuff of legend: He was an eyewitness to its invention. “Gelsinger doesn’t feel the weight of Noyce, Grove, and Moore, because he was there,” says veteran tech reporter Michael S. Malone, the author of The Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World’s Most Important Company. “He knows their flaws.”

How the Groveian principles manifest themselves today may need some rethinking. But to Gelsinger, they’re critical management tools that were dormant when he returned to the company. “These attributes are the core of what made Intel Intel, and some of them have been, I would say, minimised, homogenised, and undervalued in this period of time,” he told me in June 2021. “So I do want to harken back to bring those capabilities forward.”

Even by the standards of the tech industry, chip-making was long a business utterly dominated by white guys: Of 29 corporate officers listed in Intel’s 1997 annual report, for example, two were women and none were Black. In more recent years, the company has worked to make its staff look more like America, but—as at most tech giants—progress has been slow. Since 2012, the percentage of Intel U.S. female employees increased from 23.6% to 26.3% and African Americans increased from 3.8% to 4.9%, according to data the company has made public. (The company aims to double the women and underrepresented minorities among its senior ranks by 2030.)

In June 2021, Gelsinger named 22-year Intel vet Sandra Rivera to head up a new Datacenter and AI Group. Rivera, who spent two years as Intel’s chief people officer before taking on her new role, describes what Intel staffers are looking to get out of their relationship with the company, using terms that would have been unlikely to come up in its original heyday. “For sure, we are in an age now where our employees are looking for a deeper, richer connection to the purpose of the organisation,” she says. “They care about diversity, equity, inclusion. They care about the planet.” She adds that Grove’s concept of constructive confrontation “was probably more confrontation than constructive, or it got to that point.”

Still, she stresses that the Groveian principles, as filtered through Gelsinger’s at least slightly kinder, gentler interpretation, are key to Intel’s future: “Pat really asks us to come to the table with data and a point of view. And he’ll often say that data without a point of view is not that useful, and a point of view without data is also not that useful.”

PROGRESS REPORT

“Today, we are going to take you on a journey from silicon to superpowers. The geek is back at Intel.”

Gelsinger is keynoting an online developer event called, “Intel Innovation.” There’s a lot of news, including previews of Intel’s 12-generation processors for desktop PCs and its upcoming Arc graphics processing unit, the latter of which is an important product as Intel works to play catch-up with Nvidia in graphics and AI. The company also announces collaborations with both Google and Amazon on data-center chips.

Back in March, when Intel announced this October event, it was supposed to be a bustling in-person confab at San Francisco’s Fort Mason Centre. The COVID-19 pandemic’s unfortunate staying power forced it to go virtual, leaving Gelsinger and other executives presenting to an empty hall. When I arrive for a post-keynote face-to-face chat with Gelsinger, the place is eerily quiet.

Intel may be making news on the product front at a steady clip, but as Gelsinger and I talk, Wall Street is paying more attention to the vast expense of the company’s expansion plans and its willingness to lower its margins for the time being. Investors haven’t bought into this strategy, and Intel’s stock price reflects it. Gelsinger professes not to be too concerned: “Clearly, we have laid out a plan that is not driven by a quarterly perspective of Wall Street. I’m not expecting the praise of Wall Street.”

More than three months later, when I talk to Gelsinger again, he sounds a little more impatient with the Street’s impatience. Intel stock is still in the doldrums: As I write this, it’s down more than 20% since his arrival. In the quarterly results the company announced in January, it beat analysts’ revenue estimates by more than a billion dollars, but the stock slid anyway, a reaction that Gelsinger admits “just sort of pisses me off. But hey, I’m also being applauded by those who say, ‘Don’t manage the company by Wall Street, manage for your five-year strategy. That’s exactly what we’re doing.”

Another source of frustration emanates from Washington, D.C., where the wheels of statecraft turn slowly and Groveian principles of discipline do not apply. Eight months after the Senate passed the CHIPS for America Act, Gelsinger—who once hoped to see some of the bill’s $52 billion by the end of 2021–is impatient with the House’s lackadaisical progress on its version of the fab-funding initiative. “What have you been doing?” he asks. “Here we are in February, and we’re only debating it.” Two days after he vents, the House passes the bill, but no money will be forthcoming until the two chambers’ versions are reconciled. That could take months.

One thing that Gelsinger says is turning out to be easier than he feared is figuring out how to getting Intel’s chip manufacturing process advances back on track. There are no quick fixes: The company managed expectations by saying it didn’t expect to return to a leadership position until 2025. That’s contingent on it making steady progress in the interim, and benchmarks show its Alder Lake processors faring well against AMD’s Ryzen and Apple’s M1 Max (albeit with none of the Apple chip’s game-changing power efficiency).

As upbeat as he is about what’s ahead, Gelsinger is not one to paper over Intel’s present quandaries. Apple’s dumping of Intel chips? “It’s shameful that we lost that business because they decided they could do a better product without us.” AMD’s resurgence? “They had another good quarter, and if they have a good quarter, that means I’m not doing my job.” Nvidia’s dominance in chips tuned for AI? “We haven’t been showing up to compete.”

He does, however, punctuate every admission of failure on an optimistic note. In October, Twitter pundits mocked Gelsinger’s declaration that he hoped to someday get Apple back on Intel’s platform by building better processors than could be designed in Cupertino. He was sticking to it when we spoke early this month—it could happen “late this decade”—but he also talked about a shorter-term, less inherently risible scenario: That Intel might win part of the business for Apple-designed processors as a contract manufacturer. “They’re going to want a diversity of foundry partners, and they’re going to get more political pressure for that to be on U.S. soil,” he argues.

Even Apple partisans couldn’t scoff when Jeff Wilcox, a two-time Intel alum who’d gone on to help create Apple’s self-designed processors, rejoined Intel yet again in January. Another recent returnee, senior design engineering VP Shlomit Weiss, says that the urgency Gelsinger has instilled is tangible: “It’s different now—I think it’s different in a good way.”

For all the ways that Gelsinger’s Intel remains a work in progress, it’s already clear that he won’t be remembered as VMware’s successful CEO or the engineer who spearheaded the 486 chip. In one way or another, the future he’s charting for Intel will define his legacy. That’s true for others on this journey as well: “I do feel sort of a sense of pride, but also just responsibility,” says Greg Lavender, who served as VMware’s CTO under Gelsinger and was contemplating retirement when Gelsinger cajoled him into taking the same role at Intel. (“Pat is a very persuasive person,” he explains.)

One of the biggest milestones that Gelsinger has checked off so far has been the unveiling of Intel’s decision to construct two fabs on 1,000 acres of land in New Albany, Ohio. And the location of the January 21 announcement—the White House—underlined that the impact was not at all limited to what it meant for the company. After speaking about the news, which included Intel’s pledge of $100 million over a decade to fund a pipeline of relevant expertise at local education institutions, Gelsinger put in a plug for Congress to fund the CHIPS for America Act. Then he introduced President Biden, who called Intel’s Ohio plan “a truly historic investment in America, in American workers.”

A couple of weeks later, when I catch up with Gelsinger, he’s still radiating in the significance of what Intel is planning to do in Ohio. The 3,000 Intel jobs it intends to create—plus many more to support the new fabs’ ecosystem—are “the renaissance of heartland manufacturing,” he says. “The end of the Rust Belt, the beginning of the technology era. This resurgence of manufacturing in America, by America, for America. I’ll just tell you, this has touched a chord that was deeper and more profound than I expected.”

Every CEO wants to serve a mission that goes beyond the balance sheet, but for Gelsinger, the higher-level implications of his job are still unfolding. “It’s exhilarating, it’s challenging, it’s huge,” he says. “It’s reviving an iconic brand, but it’s also helping an industry, changing the face of the United States and technology and national security, and doing it through the middle of a pandemic and a global shortage. That’s a big honking assignment. I think we’re generally ahead of where I thought we’d be at this point, but we still have a lot of mountain to go.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

HARRY MCCRACKEN IS THE TECHNOLOGY EDITOR FOR FAST COMPANY, BASED IN SAN FRANCISCO. IN PAST LIVES, HE WAS EDITOR AT LARGE FOR TIME MAGAZINE, FOUNDER AND EDITOR OF TECHNOLOGIZER, AND EDITOR OF PC WORLD.