When you visit a chic shopping area–say, the Meatpacking District in New York or the Champs Élysée in Paris–you’ll find the best-known luxury brands of our time, from Chanel to Tory Burch. The vast majority were founded by white designers, with a distinctly Western point of view.

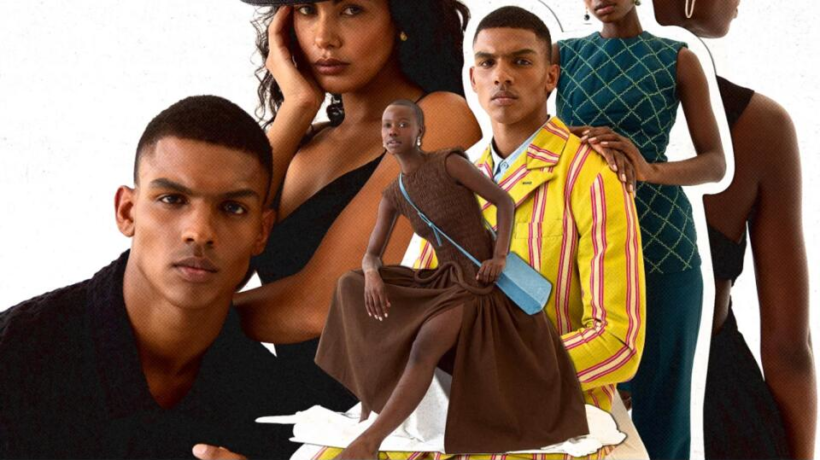

Amira Rasool thinks this is a problem; she’s on a mission to help African designers to take their place among their American and European counterparts. Four years ago, she launched The Folklore, a marketplace that curates top African designers, like Ahluwalia or Thebe Magugu. But now the company is expanding beyond single item sales, and will soon be unveiling a new platform called The Folklore Connect that makes it easy for retailers to place bulk orders from these designers to get their clothes in front of new customers.

Rasool grew up loving fashion and once aspired to become a fashion journalist. But when she attended Rutgers University, she become interested in African studies, and went on to the University of Cape Town to pursue a masters in the field. Over time, it occurred to her that she could bring her two passions together. “I studied iconic figures like James Baldwin and W.E.B. Dubois, these radical figures who dedicated their life’s work to the social and economic futures of Black people,” she says. “I saw an opportunity to amplify the voice and conditions of Black people by helping African designers increase exports from the continent.”

She began exploring the nascent, bustling fashion industries across Africa, identifying up-and-coming labels like Orange Culture and Andrea Iyamah from Nigeria, and House of Gozdawa in South Africa. She brought them onto The Folklore Marketplace, a website that enabled customers in the U.S. and Europe to shop these brands, taking a 30% commission. But she quickly discovered that it was hard to drive enough traffic to the site to make a big impact on behalf of these designers. To reach a bigger audience, she needed to connect them with bigger retailers–from Nordstrom to cool boutiques–who would carry their collections. “They already had large, established customer bases,” says Rasool.

But this turned out to be a complex endeavor. For one thing, the business infrastructure in Africa can often be challenging to navigate. Global payments systems like Stripe don’t operate in many African countries, so designers cannot receive money to their local bank accounts. Then there are issues with shipping. While DHL and FedEx operate throughout the continent, it can be extremely expensive for individual designers to send packages overseas; even in the U.S., brands and retailers get much better rates by sending large volumes of goods.

In some ways, Rasool is working to create the kind of luxury conglomerate we’ve seen in Europe and the U.S. The modern luxury industry was born a century ago in Europe as designers like Coco Chanel, Hermes, and Louis Vuitton began making expensive, fashionable clothes. Some luxury brands have become more powerful by consolidating. Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy (LVMH), for instance, owns 75 luxury brands including Christian Dior and Givenchy. Kering owns Gucci, Balenciaga, and 13 other brands. This has allowed them to invest in building new factories and landing prime real estate. The Folklore is far from achieving LVMH’s scale and Rasool isn’t interested in actually buying any of these companies. Still, Rasool believes that there is a lesson to take from the big fashion conglomerates: there is power in bringing luxury brands together, and sharing resources and logistics.

While Rasool is committed to helping African designers grow and bring wealth to their communities, she also feels that the fashion world misses out when brands have such a Eurocentric perspective. Many African designers incorporate traditional patterns, color palettes, and techniques into their work, creating aesthetics that are distinct from those of Western brands. There’s a lot of beauty that American and European consumers don’t currently have access to. “These designers are combining their heritage and aspects of their surroundings into their work,” she says. “A lot of it is fresh and new to Western people.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Elizabeth Segran, Ph.D., is a senior staff writer at Fast Company. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts