Investment banker Tom Pey lost his eyesight at age 39, when an injury from a childhood game reemerged 30 years later to cause blindness. After struggling to manage with his sudden new reality, he moved into charity work to improve equity and access for blind people. While his new blindness didn’t restrict his ability to move, he pined for a core human experience that he profoundly missed: the independence to explore. “What I had lost is not the freedom to move, but the freedom to explore the real world around me,” he says.

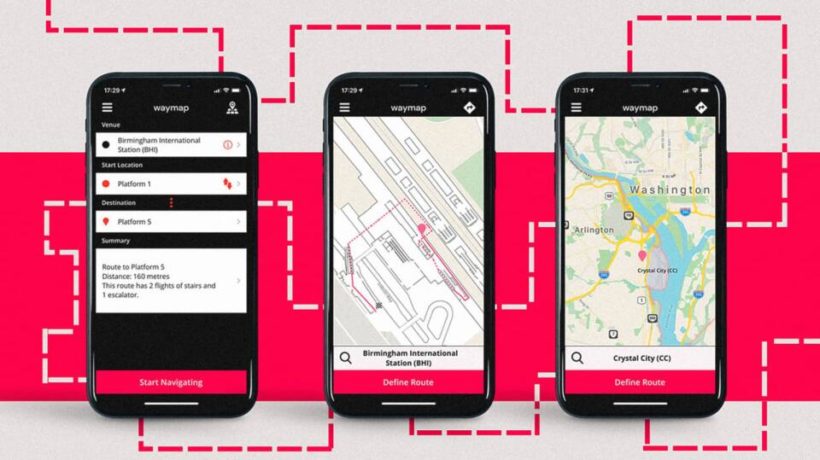

Recapturing that experience for himself and his peers was the impetus for starting Waymap, a London-based navigation app that allows visually impaired people to accurately find their way around outdoor and indoor public spaces using the inherent sensors on smartphones. This summer, Washington, D.C.’s transit system has trialed Waymap at three Metro stations and will expand to the entire network by early next year. It’s allowed blind Washingtonians to more confidently navigate for commutes and leisure activities—and to rekindle the spirit of exploration.

The idea for Waymap began when Pey was CEO of the Royal Society for Blind Children in London. Personally, he knew the challenges of navigating, in having to remember routes so precisely to avoid dangers, memorizing minute details down to, “Has Mrs. Jones cut the overhanging branch on her hedge this week?” At the same time, at the Royal Society, he consistently heard from blind people what they felt they needed in order to lead more fulfilling lives: They wanted to travel on the London Underground “like everyone else,” and young people yearned to go out on dates without chaperones. “That isn’t cool, is it?” he says of the third wheel scenario.

With a $1 million grant from Google’s charitable arm, Google.org, Pey founded Waymap, of which he’s also CEO. It’s an app that works independently of GPS or Wi-Fi, instead using the sensors already incorporated in smartphones, including the gyro, magnetometer, barometer, and accelerometer. “Each of those sensors on the phone gives us some kind of information about the way you are moving,” says COO Celso Zuccollo.

After adding a destination via voice command, users will hear audio navigation directing them in detail where to go, tailored to each person’s stride. “In five steps, turn to one o’clock,” the guide might say. To ensure the safety of an individual, accuracy is key and is especially important in open spaces where it’s easy for someone to miss a turn or not step securely onto a train car or platform. It establishes that accuracy by integrating its own highly detailed mapping. The algorithm samples 5,000 possible positions per second of where a person might be, giving an accuracy within one meter (about three feet) at all times. “That’s the difference between walking past the escalator and walking onto the escalator,” Zuccollo says.

Waymap launched in Washington, D.C. in May, trialing in Braddock Road, Brookland, and Silver Spring Metro stations, for two weeks each (Waymap has to map each trial area on its system first). The app is designed to work with multimodal transport systems, and an earlier London trial proved out the concept: Participants utilized the app to travel from one West London station to another. In D.C., the trial has been limited to Metro stations and corresponding bus terminals, testing with destinations, such as a specific bus stop, accessible bathroom, or an elevator.

But in September, it will expand to 25 stations and 1,000 bus stops, and within the first quarter of 2023, it will reach across the city’s entire transit network, which will allow for use of the app across stations and on the vehicles themselves. Then, the focus will shift to indoor spaces like malls, museums, and hotels, as part of the partnership’s ambition to make Washington “the most accessible city in the U.S.”

Of the 17 trial participants, 87% said they’d be more likely to use public transport with this system. One was Shirell Scott, 36, a beauty consultant for a cosmetics company, who lost her eyesight in 2020 due to a medical issue. Scott used Waymap mainly at the Silver Spring station and surrounding bus terminal. She found the app accurate, and it made her feel confident and secure. She says once the coverage expands, it will be useful for her commute, for errands, and for taking her nephew out downtown and to the mall. Without it, she says there are no comparable apps, and she has to have someone accompany her on every trip she makes. “It gives me a sense of independence,” she says. “I can go and get the things done that I need to get done by myself.”

That independent feeling is at the center of Pey’s mission. He says a major source of depression for blind people is the loss of freedom to explore, which becomes a vicious cycle because “going out is the greatest antidote to depression that you can get.” He aims to share the inclusive tools with other companies and organizations to help expand navigation accessibility at scale. Currently, a blind person only takes an average of 2.5 routes regularly, and Pey wants to increase that number. “At heart, everyone is an explorer,” he says, “and our job is to allow people to fulfill that dream to explore.”

BY TALIB VISRAM