Roughly a year ago, it’s likely that the new coronavirus made the jump from a wild animal to the first infected human in Wuhan, China, before spreading throughout the city, and then leaping quickly to the rest of the world. If 2020 seemed like an anomaly, it isn’t: Scientists say that another pandemic will follow at some point in the future. A new study tries to identify where it might emerge.

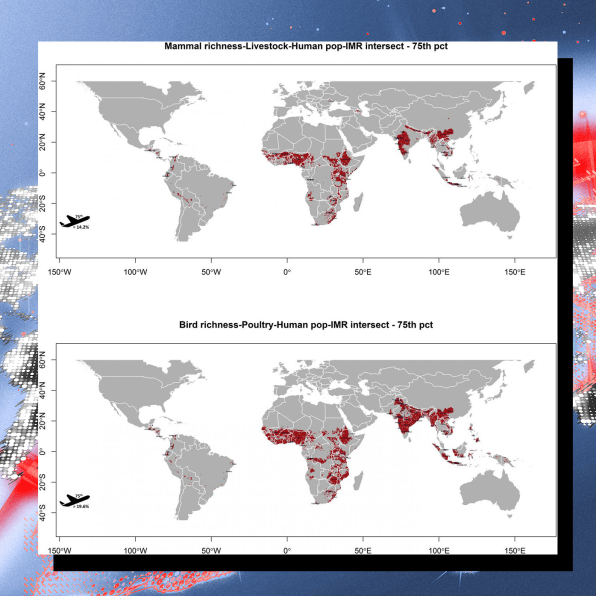

Three factors are key. In areas where the most wildlife habitat is disappearing, there’s more stress on wild animals, making disease spread more easily, and more contact between humans and animals. All of the worst infectious viruses to emerge in recent decades, including HIV, the first SARS, and Ebola, are “zoonotic,” meaning they spread from animals. (In some cases, viruses spread first to livestock, and then to humans.) Poor health systems are a second risk factor. The cities that are most at risk of being the next to launch a pandemic are also well connected globally through airports.

“Our goal was to identify those areas where the greatest amount of wildlife are sharing space with the greatest amount of people,” Walsh says. “In these spaces, humans are simultaneously putting a high degree of pressure on wildlife species and their environment and increasing their own [human] exposure to new pathogens because of the greater contact with wildlife. The result is an increase in the risk of these new pathogens ‘spilling over’ into human populations.”

A recent report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services warns that the emergence of COVID-19 was “entirely driven by human activities,” and that there are hundreds of thousands of other viruses in mammals and birds that could also potentially infect humans if action isn’t taken to protect nature and limit the possibility of them jumping species. Some could be far more deadly than SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Without action, pandemics in the future could begin to happen more often—already, new infectious diseases are emerging in humans approximately every eight months.The new study notes that areas in Africa and parts of Asia are most at risk, both because of contact between people and animals and because of the other factors: While it’s possible that a pandemic could emerge in a location with good health infrastructure, it’s more likely to happen in areas where healthcare is underfunded. “If a new spillover leads to onward human-to-human transmission, then this is more likely to go undetected in areas without good access to healthcare for all and without robust disease surveillance systems in place than in areas where these are present,” says Walsh. Cities like Mumbai, India, and Chengdu, China, are at the highest risk because they’re also major travel hubs, so once a virus emerges in humans, it could quickly spread to other parts of the globe if it’s not detected in time.

Governments can use the study to start to fill the gaps in the cities most at risk, by conserving habitat, improving health infrastructure, both for humans and vet care for livestock, and developing better disease surveillance systems that can systematically monitor pathogens (including, as a last defense, disease surveillance at airports). Societies also “need to think about ways to minimize contact, ways to ‘break the interface’ in other words, between humans and wildlife as much as possible, which means working with forest departments and other land management agencies to think about ways to reduce the sharing of space,” Walsh says.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Article originally published on fastcompany.com.