After a much more contagious coronavirus variant was discovered in the U.K. in December, scientists at Pfizer and Moderna started to study whether their newly approved vaccines would still work against it. So far, it seems likely that the vaccines will still be effective. But new variants continue to be discovered, including one in California linked to large outbreaks and one in South Africa that initial studies show may be resistant to the antibodies created by earlier strains.

The first vaccines approved in the U.S., from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, both use a new vaccine technology involving messenger RNA (mRNA). The good news: It’s something that could easily be adapted if necessary.

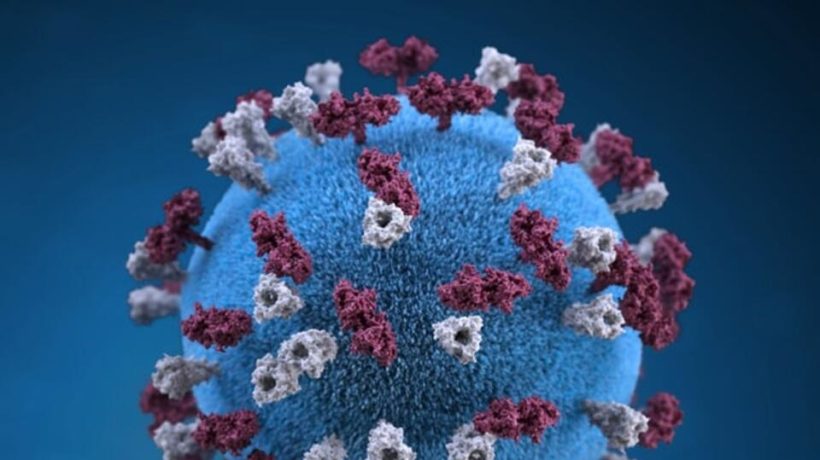

“With an RNA vaccine, it’s very easy to switch,” says Drew Weissman, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania whose early research helped make mRNA vaccines possible. The vaccines contain the genetic instructions for cells in the body to make the spike protein, the part of the virus that invades human cells, helping trigger an immune response so the body is ready to respond if it encounters the actual virus. (Other vaccines, like the one from Johnson & Johnson that is likely to be approved soon, would also be fairly simple to update, though the process would take a few more steps—and thus more time—than the new shots that use mRNA.)

To design the COVID-19 vaccine, scientists started with the genetic sequence of the virus; changing to a new variant just means plugging in new genetic code. In January 2020, researchers at Moderna were able to finalize a new vaccine days after getting the sequence. Something similar could happen now, and manufacturing it could take around six weeks.

“The only unknown is what the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] and other regulatory agencies would say,” Weissman says. Regulators might say that it’s similar to the flu vaccine, which has to change each year but doesn’t need to go through large trials again. At a recent healthcare conference, Tal Zaks, Moderna’s chief medical officer, said that he would expect a reformulated vaccine to work without needing trials. Still, it’s also possible that regulators might require additional months of testing.

So far, new variants of the virus have shown relatively few mutations, so the original vaccines should continue to work. “The spike protein is very big—it’s like 350 amino acids, so that’s big for a protein, and what that means is that there are many, many different sites that antibodies can recognize,” Weissman says. The variant in the U.K. had only a handful of mutations.

The same is true with vaccines; few people have been vaccinated so far, so the virus hasn’t had to learn to mutate to avoid the vaccines. But that could change. The disease will be difficult to wipe out because the vaccines are being distributed slowly, particularly in the developing world.

“It’s probably going to be years before we get vaccines into sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia and South America and in other regions,” Weissman says. “What can happen is that since in those areas the virus is growing freely, it’s going to keep mutating. It’s possible that someday a series of mutations might occur that the vaccine doesn’t work well [against]. And then we have to go back and we have to re-immunize the entire world.”

It’s critical to track how the virus is changing. The U.K. variant was discovered there because the country was doing more genetic screening of the virus in patients; it turns out that the variant was also already in the U.S., but officials here didn’t realize it. “We obviously missed it,” Weissman says. “We weren’t screening for it, and we should be.”

The U.S. doesn’t have a nationwide system to track coronavirus mutations. As of early January, out of the 1.4 million positive COVID-19 tests recorded each week, only around 3,000 went through genomic sequencing. Weissman says: “We need to have people dedicated to sequencing coronavirus all over the United States to see what’s developing.”

________________________________________________________________________________

Article originally published on fastcompany.com.