Sometimes it feels like a day of work conversations could be summarized into a string of what I call “word trash.”

“How’s everything?”

“I’m not gonna lie, but . . .”

So, why is that a problem, and what am I trying to solve?

“I’d come to realize that all our troubles spring from our failure to use plain, clear-cut language,” said Jean-Paul Sartre.

Here’s why word trash is a problem: If language isn’t specific, it’s hard for us to connect with it—and with each other. And it’s 2020, which for some of us has been a year already devoid of physical contact. If you want to spread connection—not Corona—I recommend you scrap the following:

According to my friend Melissa, take this offline is code for “For f*ck’s sake, stop bringing things up that aren’t on the agenda.” In “The Independent’s 10 Business Phrases Most Likely to Make You Scream” (based on a survey of 2,000 business travelers), touch base/offline topped the list. Be more specific and say “I’ll give you a call/email you about this tomorrow.”

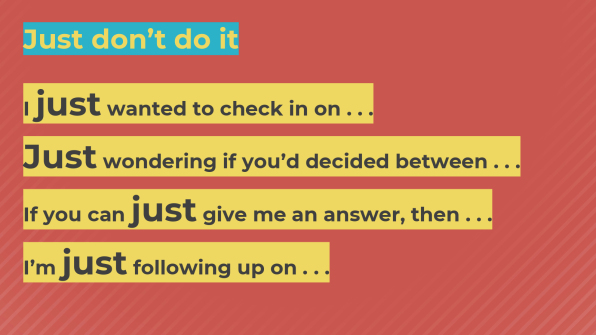

JUST

In 2015, former Google executive Ellen Leanse and her colleagues banned the word just from their communications. Why?

Leanse said she began to notice that just wasn’t about being polite. It was a subtle message of subordination, of deference: “As I started really listening, I realized that striking it from a phrase clarified and strengthened the message.”

ANY (THING/QUESTIONS)?

What’s the usual response to “Any questions?” at the end of a PowerPoint presentation? Awkward silence? Guardian journalist Rosie Ifould explains why:

“It’s too open-ended; too many possibilities abound. ‘‘What do you think about X?’ might be a more specific way of encouraging someone to talk.”

“Is there something else I can do for you today?” than if they were asked, “Is there anything else?”

There is no limit to the number of any. It’s easier to connect with and respond to a request for one something than a more abstract anything.

EVERYTHING

“How’s everything?”

Now there’s a small talk, word-trash greeting that is impossible to respond to with an honest answer. If you know how everything is, then you may also be on the run from every intelligence agency and AI project on earth. You will be hunted down for your brain. But the truth is, we don’t know how everything is, so the next time you get asked this and you want to connect, not deflect, respond with an honest answer: “I don’t know how everything is, but I am enjoying this meatball sub, thanks.” You may also respond to the word-trash question with a word-trash answer and say: “This meatball sub is everything.” No, it isn’t. It’s a meatball sub. Either our worldview of everything is narrowing—to the width of a sandwich—or we’re lying (or both).

HONEST (IF I’M HONEST. CAN I BE HONEST? NOT GONNA LIE)

Connection is more probable if we assume that our speaking partner already trusts that we are honest, rather than telling her:

My friend Mark was quick to provide his own example of how this phrase had disconnected him while working for a major European electricity company: “A senior manager I worked with did this all the time and reinforced the idea that she was constantly bullsh*tting.”

AMAZING (AND AWESOME)

Amazing is one of the phony positives that is proven to turn friends and customers off (because we feel the phony). In a text message exchange, I told a New York friend I’d taken a Citi Bike to work (something I do almost every day), to which she replied, “Oh wow that’s amazing.” I couldn’t come up with a response to that. Acknowledging that riding a Citi Bike to work was amazing would be tantamount to lying. Her amazing had disconnected us, and that ended our text exchange for the day.

ALWAYS (AND NEVER)

Dictionaries define “always” as “at all times, at one uninterrupted time, forever.”

So when you tell your partner, “You always make stupid comments,” you’re lying.

The truth? “I resent you for saying that Kim Kardashian’s butt is real and amazing.”

The truth? “You didn’t listen to what I just said.”

In an always/never conversation, no one tells the truth. And without some specifics to connect to, no one discharges their resentment. Instead, you both become charged with more frustration until one of you explodes. And then you break up or make up, or go passive-aggressive for months or years until you barely talk, until divorce or death, whichever comes first (yes, I am divorced).

SLAY (AND KILLING IT, SAVAGE, I WAS DYING)

“Friends who slay together stay together,” as some say on the gram. Or in the words of Merriam-Webster: Friends who “kill violently, wantonly, or in great numbers” together stay together. If that sounds savage, it’s because it is. Death talk is slaying our connection. We are killing it.

Look up the top tweets containing the word slaying, and you’ll find a juxtaposition of hyperbole with homicide:

“Police identify Ottawa County slaying victim”

Let’s be honest, Beyoncé has been slaying FOREVER. pic.twitter.com/YmtnDIzio5

— Marie Claire (@marieclaire) October 18, 2018

One person is dead, one person is killing it, and the line between the two is thin and gray. Marie Claire’s tweet is also an example of how to abstract and disconnect three times in eight words: First, there’s let’s be honest (let’s stop lying), then there’s forever (aka always), and third, season the sound bite with some slaying.

There is a funny side to all this death talk, but there is also a harmful side that we ignore to the detriment of our well-being. Normalizing the use of I was dying, slaying, and killing it reinforces and normalizes thoughts (and associated feelings) of death. It’s mindless hyperbole that disconnects us from the truth and from each other.

SHOULD (AND OUGHT)

“I should get my MBA.”

“You/I should read that book.”

“I should go.”

In her book, The Top Five Regrets of the Dying, palliative-care nurse Bronnie Ware tells us the number-one deathbed regret is having lived a life of shoulds and ought to‘s, aka:

If you can work on trashing your shoulds, you will have taken a step toward a regret-free life. Shoulding yourself (or others) means taking a moral dump on yourself (or others). Throw out the shoulds and you’ll eradicate some of the moralizing that disconnects you both from the truth of your feelings, and from others.

HATE (IN HATE TO SAY IT, HATE TO BREAK IT, HATE TO TWEET IT, HATER)

These are all examples of word trash that act as “emotional disconnectors”—words loaded with emotional associations that bring down the vibe of the conversation, tweet, or article we are reading.

The second-to-last time Trump tweeted with an I hate, it was in this ego-boosting lie (lie because he didn’t hate saying this):

I hate to say it, but the Republican Convention was far more interesting (with a much more beautiful set) than the Democratic Convention!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 27, 2016

“I hate to say it” is a word-trash lie. Stop hating. Say it.

Article originally published on fastcompany.com.