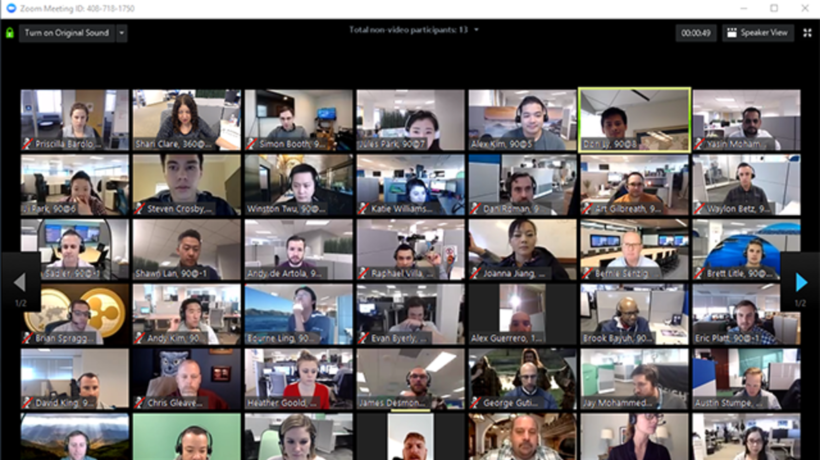

Zoom has become the go-to video conferencing app for most information workers who are currently working from home due to Covid-19.

Zoom has been considered the safer option for using end-to-end encryption in comparison to other platforms. In simple terms, this means that when conducting video calls via Zoom, no one else can view the call without authorisation.

In the past, the platform has assured its users that its communications are encrypted. However, it has since been discovered that this is not necessarily true. According to a media report by The Intercept, Zoom is in fact using its own definition of the term – one that lets Zoom itself access unencrypted video and audio from meetings. According to the Zoom website and its security white paper, Zoom offers reliability, ease of use, and at least one very important security assurance: As long as you make sure everyone in a Zoom meeting connects using “computer audio” instead of calling in on a phone, the meeting is secured with end-to-end encryption.

The reality however is that the service actually does not support end-to-end encryption for video and audio content, at least as the term is commonly understood. Instead, it offers what is usually called transport encryption. This kind of encryption aims primarily to provide privacy and data integrity between two or more communicating computer applications.

For a Zoom meeting to be end-to-end encrypted, the video and audio content would need to be encrypted in such a way that only the participants in the meeting have the ability to decrypt it. The Zoom service itself might have access to encrypted meeting content, but wouldn’t have the encryption keys required to decrypt it (only meeting participants would have these keys) and therefore, would not have the technical ability to listen in on your private meetings. This is how end-to-end encryption in messaging apps works.

According to Matthew Green, a cryptographer and computer science professor at Johns Hopkins University, group video conferencing is difficult to encrypt end to end. According to Green, this is because the service provider needs to detect who is talking in order to act like a switchboard, which allows it to only send a high-resolution videostream from the person who is talking at the moment, or who a user selects to the rest of the group, and to send low-resolution video streams of other participants. This type of optimisation is much easier if the service provider can see everything because it is unencrypted.

Green points out to The Intercept that “If it’s all end-to-end encrypted, you need to add some extra mechanisms to make sure you can do that kind of ‘who’s talking’ switch, and you can do it in a way that doesn’t leak a lot of information. You have to push that logic out to the endpoints,”.

He also pointed out that end-to-end is not impossible for video calls as it is currently by Apple through FaceTime.

What this means is that Zoom has the technical ability to spy on private video meetings and could be compelled to hand over recordings of meetings to governments or law enforcement in response to legal requests. In addition, Zoom does not publish a transparency report as currently done by companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft. Transparency reports describe exactly how many government requests for user data they receive, from which countries, and how many of those they comply with. This allows users of these services to know the extent to which their data is used.

Zoom has now been called upon by data advocacy organisations to release a transparency report to help users understand what the company is doing to protect their data.