It’s the weekend, and you decide to pay a visit to your grandma, who lives alone. When you arrive, however, you realize she has another visitor, and you hear through the door the two of them laughing. You don’t make anything of it until you walk in and find that the visitor, sitting across the dining table from grandma, is a humanoid robot—and it’s laughing at your grandma’s joke.

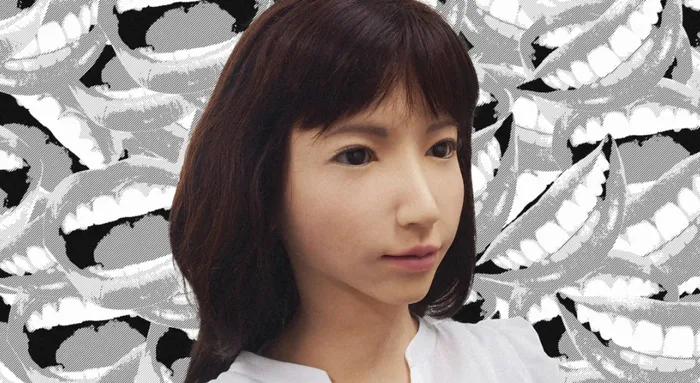

This isn’t going to become a reality this year, or in the next 10 years, but it’s exactly the kind of scenario that a team of scientists is working toward. Researchers at Kyoto University in Japan are teaching a humanoid robot how to laugh in response to a human laughing. The robot, named Erica, can detect when a person is laughing, decide whether it’s appropriate to laugh in return or not, and choose to respond with two different kinds of laughs: a small chuckle and a more boisterous giggle.

The research, which was recently published in the journal Frontiers in Robotics and AI, was done on a humanoid robot that has a synthesized human voice and can blink and move its eyes while conversing with humans. If the thought of a robot maniacally laughing at your jokes sounds disturbing to you, that’s because it is . . . but the scientists are hoping it can help build more empathic AI systems.

Think of a robot today and you will likely associate it with tedious tasks, like stacking heavy boxes in a warehouse, harvesting vegetables on a vertical farm, or even unclogging your pipes. But with a domestic robot industry that’s projected to reach $19 billion by 2027, more complex, empathic robots have entered the picture. ElliQ, for instance, is designed to tackle loneliness among the elderly, and Ollie’s creators claim it can stimulate patients with dementia or Alzheimer’s.

With Erica, too, empathy was key. “One of the ways we show how we understand emotion or understand a situation is through laughter,” says Divesh Lala, one of the study’s authors. Studies have shown that when one person imitates what another person is doing, the act, known as mirroring, can build a strong rapport between the two people. In this case, Erica was trained to mirror a human’s laugh so it can bond with people. The scientists gathered data from over 80 dialogues between male university students and the robot, which was originally operated remotely by four female actors. The dialogues were then analyzed and various laughs were categorized as “social” (like the kind where you laugh just to be polite or because you’re embarrassed) and “mirthful” (like that genuine giggle when your best friend cracks a good joke).

The scientists then trained the algorithm to distinguish the basic characteristics of each type of laugh—like a quieter titter when you’re being polite—in order to mirror them accordingly. “If you assume every laugh is equal, you’re going to respond to everything, but if you respond to nothing, it’s also embarrassing,” says Lala. “If a robot can distinguish between the two, it’s a useful finding.”

On its own, the laughing algorithm is pretty limited, but if you integrate it with other features like natural language processing and back-channeling (a nod, for example, or periodic verbal acknowledgments to show that the robot is listening), you might eventually end up with a conversational robot that could help older people fight social isolation or, as Lala ventures, teach social skills to neurodiverse people. “If they talk with a robot, maybe they can practice laughing at the right time, but you got to be careful with this, you don’t want to be relying too much on the robot,” he cautions.

It’s worth noting that none of this has anything to do with actual humor. Erica cannot discern your corny dad joke from your witty pun. At least not yet. The algorithm wasn’t trained to process the meaning of words, just laughs. “Erica doesn’t understand the kind of sense of humor, but if she reacts to the user’s laugh, maybe the user feels [like] she understands something,” says Koji Inoue, the lead author of the study.

Next up, the team wants to add different kinds of laughs to Erica’s portfolio and connect her capacity to process language with her ability to laugh accordingly, so she could decide what’s funny and what isn’t based on the meaning of the words. “Our target is human-like interaction,” says Inoue. A fully conversational robot with a silly sense of humor may not be ready in time for your grandma to give it a whirl, but then wait a few decades, and you may find your own self at that dining table, cracking jokes with a robot named Erica.