Former Facebook employee James Barnes is part of a team that’s tapping big data to nudge critical voters to the polls—amid intense efforts to keep them home.

Starting in August 2019, you may have seen an ad in your Facebook news feed asking you to take a news quiz. If you didn’t know who controlled the Senate, for instance—about 30% of people didn’t—you would be classified as most persuadable, and you would become part of one of the largest and most sophisticated experiments of its kind.

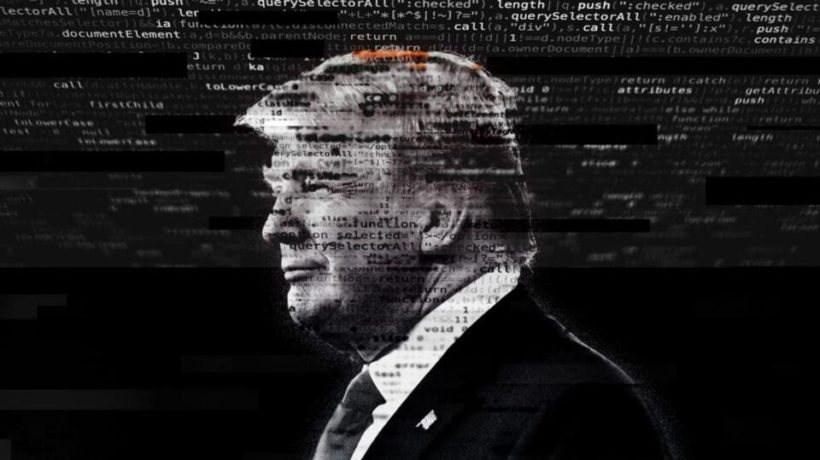

On the internet, we’re subject to hidden A/B tests all the time, but this one was also part of a political weapon: a multimillion-dollar tool kit built by a team of Facebook vets, data nerds, and computational social scientists determined to defeat Donald Trump. The goal is to use microtargeted ads, follow-up surveys, and an unparalleled data set to win over key electorates in a few critical states: the low-education voters who unexpectedly came out in droves or stayed home last time, the voters who could decide another monumental election.

By this spring, the project, code named Barometer, appeared to be paying off. During a two-month period, the data scientists found that showing certain Facebook ads to certain possible Trump voters lowered their approval of the president by 3.6%. For the frantic final laps, they’ve set their sights on motivating another key group of swing-state voters—young Democratic-leaning voters, mostly women and people of color—who could push Joe Biden to victory.

“We’ve been able to really understand how to communicate with folks who have lower levels of political knowledge, who tend to be ignored by the political process,” says James Barnes, a data and ads expert at the all-digital progressive nonprofit Acronym, who helped build Barometer. This is familiar territory: Barnes spent years on Facebook’s ads team, and in 2016 was the “embed” who helped the Trump campaign take Facebook by storm. Last year, he left Facebook and resolved to use his battle-tested tactics to take down his former client.

“We have found ways to find the right news to put in front of them, and we found ways to understand what works and doesn’t,” Barnes says. “And if you combine all those things together, you get a really effective approach, and that’s what we’re doing.”

As the pandemic has glued voters to their phones and screens and added unprecedented hurdles to campaigning and voting, the 2020 digital arms race has become bigger and uglier than many had expected. The presidential and congressional campaigns have spent more than $1 billion on digital ads this year, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, during what’s become the costliest election in history. In the final weeks, the online ad shopping spree has grown so intense that in many battleground states, YouTube ads are sold out.

The president had a running start. On top of what his former campaign manager called a “Death Star” of data and campaign infrastructure, the Trump campaign has devoted far more of its resources to digital advertising than the Biden effort, and spent a whopping $142 million on Facebook ads so far, outpacing Biden’s outlay of $89 million, according to an analysis of the Facebook ad archive.

A multitude of outside anti-Trump groups such as Acronym have spent millions more to fill in the gaps. Earlier this year, Priorities USA and Color of Change launched a $24 million digital advertising campaign aimed at exciting Black voters in swing states. American Bridge and Unite the Country, two of the other largest progressive PACs, have tapped Mike Bloomberg’s political ad tech startup, Hawkfish to wage their own data-rich digital onslaughts through Election Day. Acronym was first out of the gate, and is thought to be the Democrats’ most advanced digital advertising project. By the election it promises to have spent $75 million on Facebook, Google, Instagram, Snapchat, Hulu, Roku, Viacom, Pandora, and anywhere else valuable voters might be found.

For a year that money went toward targeting low-information voters in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and North Carolina, but by the end of the summer, the Barometer team saw its persuasion powers diminishing; they guessed that they couldn’t budge the president’s approval rating any lower. So Acronym redirected that cash to motivate another critical audience of low-information voters: new or unlikely Democratic-leaning people thought to be unexcited about Biden and his running mate, Senator Kamala Harris. Barometer’s scientists have identified 1.8 million such voters in six states—mostly women of color younger than 35 across Acronym’s original five target states, plus Georgia.

With more than $1 million per week in Facebook ads during the homestretch, “we’re trying to boost their enthusiasm,” says Kyle Tharp, Acronym’s VP of communications.

Despite upbeat polls and record early turnout numbers, Acronym’s battle was never going to be easy. These voters are thought to be some of the least-excited, and while Acronym has identified them as the easiest to persuade, they are also highly susceptible to the sort of BS that can keep voters home. Research has shown that low-information voters are not only less likely to vote but more likely to believe falsehoods; sometimes they’re called “misinformation voters.” And deterring voters with falsehoods and fear may be easier than motivating them with facts and hope. A false claim about voting, for instance, is much easier to spread on Twitter—or by anonymous text message—than it is to correct.

And there’s no end to the BS. While Team Trump floods swing states with anti-Biden ads meant to dampen enthusiasm among Democrats (attacks on his and Harris’s record on criminal justice reform, for instance), the candidate and many others are waging hybrid war, pushing extreme rumors of child-trafficking cabals and falsehoods about voter fraud and mail-in ballots—a handy way to erode the confidence and will of already hard-to-motivate voters.

“We have three major voter suppression operations underway,” a senior Trump campaign official told Bloomberg in the days before the 2016 election, referring to a barrage of disappearing “dark posts” that painted Hillary Clinton as a racist and targeted white liberals, young women, and African Americans. The Russians took a more direct approach: After identifying groups of people of color using Facebook’s tools, one Russian-backed page microtargeted them with an ad on Election Day: “No one represents Black people. Don’t go to vote.”

These are some of the same types of voters that Barnes and his team are trying to motivate. “I think we’re trying to not just fill the gap that other [progressive campaigns] aren’t filling, from a targeting perspective,” he says, “but we’re also trying to find the people who we think are pretty vulnerable to hearing this information and get the facts in front of them.”

REMEMBER THE ALAMO

Barnes comes with a special skill set and a quiet, fierce sense of urgency. The last time he targeted impressionable voters with relentlessly tested Facebook ads and reams of data was inside Project Alamo, the Trump campaign’s big-data digital operation. Barnes is eager to put 2016 behind him, but readily acknowledges the work he did then was “groundbreaking.” Trump had his Twitter, but no campaign had before used Facebook to persuade voters, find more of them, and raise money like Trump’s had. At times a dollar in ad spend translated to donations of $2 or $3. Facebook’s then-head of ad technology wrote in an internal memo that it was “the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser. . . . They just used the tools we had to show the right creative to each person.” In a since-deleted tweet, Trump’s digital director, called Barnes “our MVP.”

Barnes had been a Republican all his life, but he did not like Trump; he says he ended up voting for Clinton. The election, and his role in it, left him unsettled, and he left Facebook’s political ads team to work with the company’s commercial clients. He learned how Cambridge Analytica had paid a couple of researchers—including one whom Facebook would later hire—to serve data-scraping Facebook quizzes to thousands of Facebook users, and used a cache of 87 million Facebook profiles to motivate some unlikely voters and suppress others. (Barnes worked alongside Cambridge Analytica employees but has said he wasn’t aware of any voter suppression efforts or ill-gotten data at the time.)

Source: FastCompany.com