To determine your breathing rate, the new application inside of Google Fit directs you to take a bust-length portrait-style photo of yourself.

Heart and respiratory rate tracking is nearly ubiquitous on sleek fitness bands and bulbous smart rings. Where those kinds of metrics are not yet universal is on smartphones. On Thursday, Google announced plans to change that by launching new software that can capture your heart rate and breathing rate through your phone’s camera lens. The technology will be rolled out inside of Google Fit, the company’s health tracking platform, on Pixel phones.

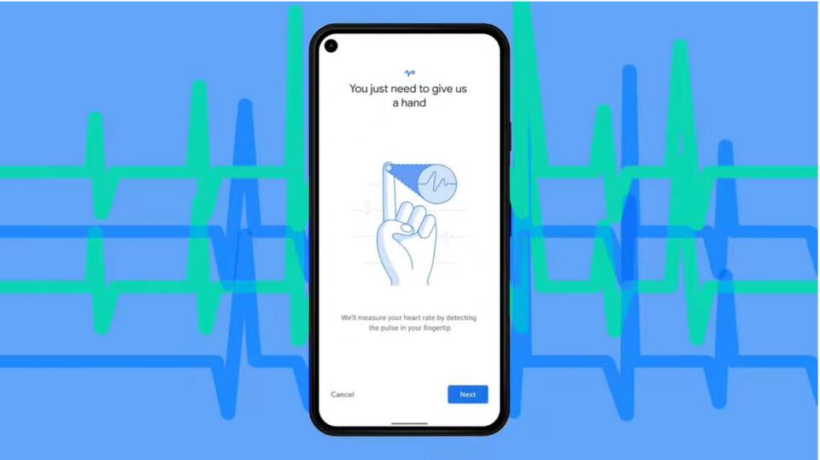

To determine your breathing rate, the new application inside of Google Fit directs you to take a bust-length portrait-style photo of yourself. This allows the phone’s camera to see how fast your chest is rising and falling, from which it can calculate respiratory rate. To capture heart rate, you place your fingertip over the camera. The app then follows changes in skin color to measure blood flow. It uses photoplethysmography, the same technology as existing apps on the market that track skin-color changes to pick up on biological signals.

The company says it has clinically validated the technology and will be publishing a paper based on its research once it goes through peer review. Google’s health team indicated that breath rate was accurate within one breath per minute. The company also made a point to show that its technology worked across different skin tones within an average error rate of 2%. Accuracy seemed to be slightly higher for medium skin tones.

For now, this technology is only on Pixel phones with the latest version of Android. It is being categorized as a wellness feature inside of Google Fit rather than as a clinical device. Analyses are conducted on the device, but if users want to store their heart or respiratory rate, that data is stored in the cloud. The company plans to roll out the new measurement tools to more Android phones once it can be sure that its technology will work with another phone’s sensors. Down the road, Google may seek approval for its technology from the Food and Drug Administration as a medical device.

Google already provides heart rate monitoring through Fitbit, its recently completed acquisition, though the team at Google Health hasn’t started working with the wearable company yet. Google Fit reports having “millions” of monthly users across Android, iOS, and Wear OS (many of whom are likely clocking in on wearable devices). Meanwhile, Fitbit, per its last update, has roughly 30 million users. So why put this technology on your phone at all?

Google product manager Ming Jack Po says the company wants to make these kinds of measurements more available to people who only have cell phones. He believes that for people who cannot afford high-tech wearables, snapshots of heart and breath rate can tell a lot about their health. “I’ll use myself as an example,” Po says. “I have a Peloton bike and I’m interested in how high my heart rate goes when I really exercise, so I might use it multiple times a day to figure out if I am really biking near my limit.” He says other people may check their heart rate just once a week to get a sense of whether consistent exercise is lowering their overall resting heart rate—a signal that’s linked to cardiovascular health.

“If you think about what doctors do, we get a measurement every six months when we show up to the office and we base clinical decisions on that,” Po says. This is partially true. Doctors do keep track of single measurements like heart rate, blood pressure, and aspects of breathing over time. However, they make diagnostic decisions through assessing data points in context with each other, not off of a single biometric.

If you’re a woman and you have a resting heart rate that’s on the higher end, for example, it may mean that you have cardiac disease. It could also mean you’re pregnant. Similarly, a low heart rate can mean you’re incredibly fit. But that low heart rate may also be caused by a medication or be the result of a rare infection. Ultimately, heart rate and respiratory rate are most meaningful when they are surrounded by other data points, like blood pressure and cholesterol readings. Wearables tend to collect more of these data points and can do so continuously. Because they can gather data passively, these devices are better at showcasing changing trends in your health data, like if your temperature is up slightly this week as compared to the three weeks prior.

It appears that Google’s engineers want to make use of more smartphone sensors to pick up on health metrics that can provide that context. We’re likely to see other such smartphone innovation in the future (especially as Google starts working with Fitbit). In the meantime, this latest tech launch from Google reveals the company is pushing toward making digital health products far more accessible.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Article originally published on fastcompany.com.