Tripadvisor. Expedia. Booking.com. Google. No matter where you begin the process of booking your next vacation, it’s always the same: You type where you want to go into a search bar, then you choose your rental from the available options. And that’s even been true for Airbnb, the gargantuan home-sharing platform that’s booked 10 million years’ worth of stays to date.

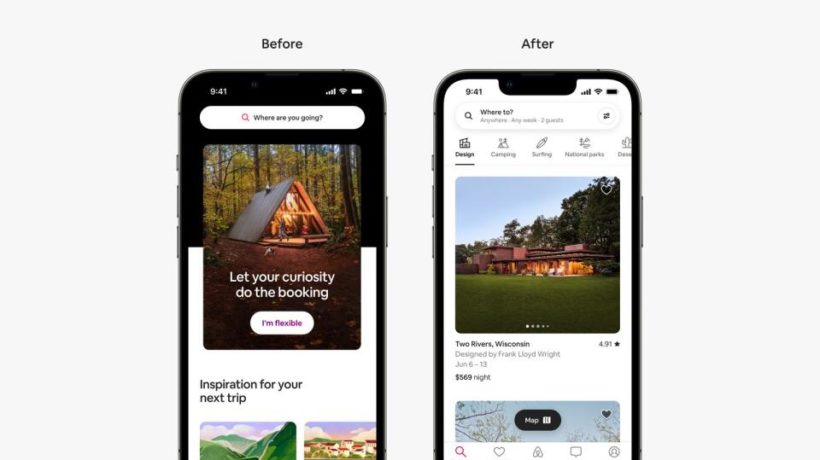

Last week, that paradigm changed, as Airbnb unveiled its most significant redesign since its startup days. The new design de-emphasizes the importance of the search bar that asks where you want to go, and instead nudges you to pick from 56 “categories” that unpack what you want to do when you get there—wherever there is.

Those categories include activities like camping and surfing, locations like beachfront or vineyard, and home designs like yurts or tree houses. The entire design is meant to encourage you to think more broadly about the locations that can offer a satisfying vacation, while promoting the properties themselves as the unique experiences worth taking a trip regardless of the city they’re in.

“We’re in a hundred thousand cities. Very few people can think to type in more than 20 places [into a search bar],” says Brian Chesky, CEO of Airbnb. “So what happens? Everyone ends up going to the same places. Everyone goes to Vegas and Miami and New York and Paris and Rome and London.”

Don’t let the still images, topped with search bars, in this story fool you. During an hour-long demo on the new platform last week, I was surprised by how little I noticed the search bar at all. Especially when you browse on a desktop, it disappears due to the prominence of categories. Tap on Airbnb’s homemade icons for these categories, and you see a list of its most tantalizing properties with their earliest date of availability. In moments, you’ll be hooked.

“Historically, if you want to go wine tasting, you have to type in, like, Sonoma, or France . . . and now you can just click on vineyards and realize there’s actually vineyards all over the world,” says Chesky. “I’ve always had this idea in my head that we can also point demand to where we have supply and have a much more aspirational . . . way to travel. But the problem was before the pandemic, [travel] was so habitual.”

As Chesky explains, Airbnb has found people are now traveling with less rigid schedules, while others are taking advantage of Zoom offices to travel all the time. While Airbnb has adapted well to the moment as the company’s revenue is up 70% year-over-year, Chesky believes that this is the window to be aggressive as a company and capitalize on new behaviors.

“We’ll be more in the business of inspiration,” he says.

Building these categories—which will expand over time—was more than a superficial design exercise. The company used AI to analyze the text and imagery of 4 million properties, which even dug into comments to understand that a particular location might be good for golfing. This approach also helped spot some of the hyper specific amenities like a “chef’s kitchen” and “grand pianos” that Airbnb is using categories to promote.

Ultimately, these amenities are meant to make you consider staying somewhere you wouldn’t have considered before. For instance, Airbnb’s development team pointed out that for $600/night, I could stay in a home with a full professional recording studio in Riverdale, GA. I could get an entire home for what I might pay for an hour of studio recording time in any major city. Whether you want to record a track, or look out of a mid-century modern home into a forest, or live off-the-grid on the beach, Airbnb’s location-agnostic categories are there to help. (And for any stay of over a week, Airbnb is unrolling a feature that can split your stay across two nearby homes—an update that offers 40% more housing options for travelers in the company’s early tests.)

When asked about the impact these changes might have on the Airbnb business, Chesky admits that it’s very difficult to model. But over time, he believes more enticing properties will lead to more overall bookings on Airbnb. And in five, or maybe ten years, he believes that search bars will no longer lead to the majority of Airbnb’s own bookings, as they do today—even if we’ll always have both the need and desire to stay in specific cities.

But my bigger concerns are regarding the potential downstream effects of Airbnb’s updates.

With its new feed that’s location agnostic, hosts don’t just have their homes compared to others in their own area. Suddenly, they’re competing with a literal world of houses—a world where property prices might vary greatly, which impacts how much anyone can sink into decorating their home. Investors have already taken over many Airbnb listings, and it’s easy to imagine this new Airbnb forcing its hosts to invest significantly in their own properties just to keep up with fresh competition. It seems that the more casual Airbnb hosts—people who rent out more mundane apartments or homes on a whim—could lose out in this scenario.

“I think that what it’s going to do is it’s going to encourage hosts to compete on more than just price,” Chesky says. “It’s going to encourage hosts to compete on more than just location proximity. It will encourage hosts to offer something that’s unique, something that’s different, something that’s one of a kind.”

Ultimately, he says such updates come with “intended consequences and unintended consequences,” but that while hotels have commoditised the room you’re in to the point that you don’t even see an actual picture of your unit, he intends to do the exact opposite with Airbnb. These updates can allow every property, no matter the locale, to have a chance to shine.

The other potential effect is on communities themselves. Airbnb has already impacted high tourist destinations: Areas like Sonoma are littered with Airbnb protest signs, posted by residents who are sick of rentals. A recent story in The New York Times demonstrated how Joshua Tree was getting flooded by cookie-cutter modernist rentals, which encroached on the serene desert landscape. I ask Chesky if he’s concerned that Airbnb’s redesign could bring similar problems to small town America, if it might over-popularize quiet areas at the expense of their identity.

“The reason a lot of people go to Sonoma is actually that Sonoma is super famous—as is Joshua Tree. And so people are typing in Sonoma and Joshua Tree into Airbnb,” says Chesky—who goes so far as to call Joshua Tree “the brand desert.” “I guess the point is that what we’re trying to do is move away from the place you think to type, to redistribute and spread out. If we send everyone to Geneva, Ohio, then yes, we will probably flood Geneva, Ohio. The point is, though, to not to send everyone to any one place, and not to limit search to the places people can think of.”

The larger trap Chesky is worried about is that Airbnb becomes stagnant and stops updating its platform, and that it misses its own opportunity to impact not just its own bottom line, but the very way people value any given location on this planet.

“We don’t know with 100% certainty how this product will work. We’re confident. But the point is, we’re still willing to take the risk . . . to make a huge change that will probably affect the sector,” says Chesky. “And if it turns out that unintended things are happening, and they will, we’re going to adapt the product. We’re not going to put our head in the sand.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Wilson is a senior writer at Fast Company who has written about design, technology, and culture for almost 15 years. His work has appeared at Gizmodo, Kotaku, PopMech, PopSci, Esquire, American Photo and Lucky Peach