Since Patagonia’s founding in 1973, Yvon Chouinard and his family have been its owners. Now, almost 50 years later, the company is announcing that the Chouinards are transferring all ownership to two newly created entities in an effort both to cement the company’s values in its operating structure and step up its fight against the climate crisis. All voting stock (about 2% of the total) is now controlled by the Patagonia Purpose Trust, while the other 98% is under what’s called the Holdfast Collective.

The goal behind the Patagonia Purpose Trust is to create a permanent legal structure to enshrine the company’s purpose and values, so that there is never deviation from Chouinard’s intent—and to make sure the company continues to demonstrate that capitalism can work for the planet. Meanwhile, the company says that all annual profits that are not reinvested back into the business—which they estimate to be about $100 million per year—will be distributed by Patagonia as a dividend to the Holdfast Collective (which is designated as a 501(c)(4) organization) to fund grassroots environmental organizations, invest in businesses, and support political candidates that all work to protect nature and biodiversity, support thriving communities, and fight the climate crisis.

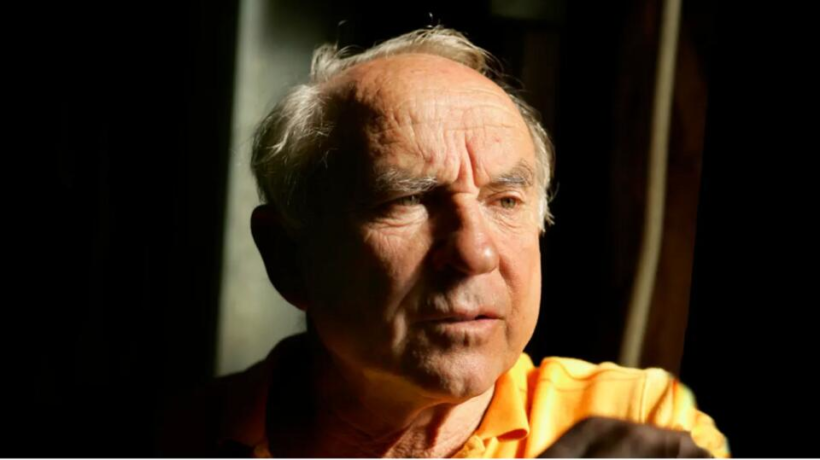

“It’s been a half-century since we began our experiment in responsible business,” Chouinard said in a statement. “If we have any hope of a thriving planet 50 years from now, it demands all of us doing all we can with the resources we have. As the business leader I never wanted to be, I am doing my part. Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth, we are using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source. We’re making Earth our only shareholder. I am dead serious about saving this planet.”

In a letter to employees, Chouinard wrote that when searching for ways to put more money toward the climate crisis while keeping the company’s values intact, there weren’t any good existing options. Selling the company and donating all the profits would help—but in no way guarantee—the survival of Patagonia’s values. Going public was never an option, thanks to Wall Street investors’ never-ending pressures to create short-term gain at the expense of long-term responsibility.

So, as with so many other things Patagonia has done over the decades, the company decided to create its own option. “Instead of ‘going public,’ you could say we’re ‘going purpose,’ ” Chouinard wrote. “Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth for investors, we’ll use the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source of all wealth.”

Perhaps the most obvious, yet unmentioned, line of succession would be to simply pass the company on to his children, Fletcher and Claire. But the elder Chouinard has always bristled at any ties between the family and the company’s wealth, and absolutely hates the notion of being called a billionaire. In that sense, this move toward a new model altogether wears its goals in a clear way that multigenerational family ownership just can’t embody, and preemptively answers cynicism or criticism of the company’s motives.

While, in some ways, the new ownership structure represents a radical change for Patagonia, in others it makes perfect sense as a natural evolution. This is a company that has always done business on its own terms. (The same can be said of the Chouinard family.) Patagonia cofounded 1% for the Planet, which has led thousands of companies to commit 1% of annual sales to environmental causes. It helped pioneer the very definitions of benefit corporations. Its embrace of organic cotton and recycled materials in apparel led to their widespread proliferation—and it has led the push for the certification for regenerative organic agriculture. Even in its workplace practices, Patagonia has been decades ahead of everyone, seeing as how it was founded on the idea of employee “flex time” (so they could go climbing and surfing) and started its company daycare program in 1984.

In 2018, it changed its mission statement to read, “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.” A year later, Chouinard was already working out just how Patagonia could remain consistent in its values and fight the climate crisis beyond his lifetime. “We’re a billion-dollar company, over a billion, and I don’t want a billion-dollar company,” Chouinard told me at the time. “The day they announced it to me, I hung my head and said, ‘Oh God, I knew it would come to this.’ I’m trying to figure out how to make Patagonia act like a small company again.”

For now, the Chouinards, along with the company’s board, will lead both the Purpose Trust and the Holdfast Collective. The challenge will be to make sure the structure is sound enough to ward off unforeseen changes over the years and even decades—to prevent potential future abuse for, say, where “reinvesting in the business” could translate to “big salary raises for top brass”—and to avoid the kind of quagmire currently enveloping Ben & Jerry’s, where the best-intentioned, well-designed structure arrangements to preserve company values are being overpowered.

In terms of the Holdfast Collective, in the case of potential abuse, if the company board doesn’t remove the CEO, the Patagonia Purpose Trust would be empowered to do it. The company says that because there are no individual beneficiaries and the stock can never be sold, there is no financial incentive, or structural opportunity, for any drift in the Purpose Trust’s objective of maintaining Patagonia’s purpose. In addition, an independent “Protector” has been named who is empowered under the trust to monitor and enforce the trust’s purpose.

Whether it’s climbing mountains or finding a better way to make apparel, Chouinard—and by extension his company—has never been afraid of a challenge. Patagonia’s leadership is hoping that this move, like so many of its past ones, provides inspiration to other companies looking for a way to reconcile capitalism and the climate crisis. As Chouinard told me a few years ago, “It’s a never-ending summit. You’re just climbing forever. You’ll never get to the top, but it’s the journey.”

As the company prepares to mark the 50th year of its own journey, it’s once again reached the edge of the corporate map, and, in a move of capitalist cartography, is charting a new path.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Beer is a staff editor at Fast Company, covering advertising, marketing, and brand creativity.