“Zoom is sort of like a verb when it comes to videoconferencing, right?”

That’s Eric Yuan, the founder and CEO of Zoom, speaking—and a moment later, he retracts the claim: “I guess that’s too strong.” But he was right the first time. Thanks to its bacon-saving ubiquity during the COVID-19 pandemic, Zoom really is in the rarefied company of Google and Photoshop—products so synonymous with their categories that they’ve transcended mere nounhood.

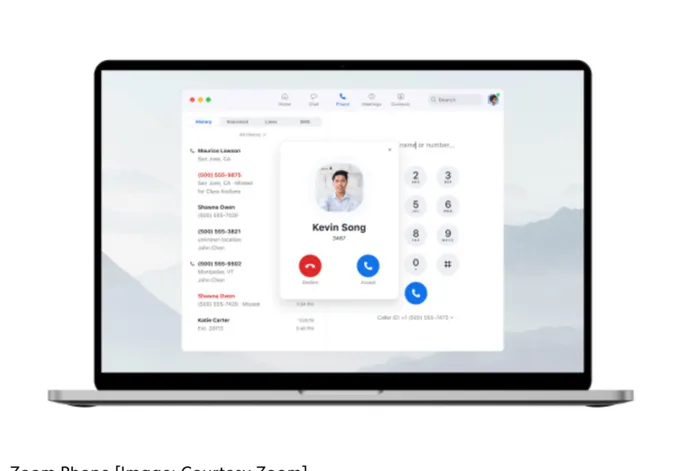

Zoom might have a symbiotic relationship with online meetings, but that doesn’t mean it’s a one-trick pony. Way back in 2014, for instance, the company introduced ZoomPresence, a video collaboration service for conference rooms; today, under the name Zoom Rooms, it offers everything from a virtual receptionist to the ability to reserve a desk. Zoom Phone, launched in 2018, is a cloud-based replacement for old-school desk phones. Then there’s Zoom Chat, a Slack-like business messaging tool—which, as of today, is being renamed Zoom Team Chat to emphasize that it’s not just for use within video calls.

The chat service’s rebranding is part of a larger Zoom initiative to convey all the communications problems its software can solve. “The good news is, the trust is already there,” says Yuan, in a rare interview we conducted via—what else?—a Zoom call. “Because of many years of hard work, and also the pandemic crisis, [customers] understand that Zoom is a great company that truly helps people connect.” Still, he adds that Zoom has many happy users who think of it solely as a videoconferencing service. Now the company wants to fix that misperception.

From a messaging standpoint, the centerpiece of this effort is a new variant of the Zoom logo. It ditches the two Os in “Zoom” for six encircled icons, turning “Zoom” into “Zoooooom.” Each icon represents a Zoom product: Team Chat, Phone, Meetings, Rooms, Events, and Contact Center. (Don’t feel guilty if you didn’t know that the videoconferencing product we think of as Zoom is really named Zoom Meetings—I didn’t until I wrote this article.)

The “Zoooooom” visual representation of Zoom’s breadth of capabilities will be featured in a new ad campaign spanning digital, social, streaming, and out-of-home media such as billboards. It will also show up inside the Zoom experience itself—for example, you might see it while waiting to be let into a meeting.

“This brand expansion is indicative of the Zoom of today, which is so much more than meetings,” explains Ben Torres Ezrick, who joined Zoom as head of brand marketing in May, after more than eight years at Google. (As long as it was refreshing its logo, the company also switched out its signature light blue for a darker shade to “enhance legibility and advance accessibility on our platform for people of differing vision capabilities,” says Torres Ezrick.)

The goal is not just to communicate Zoom’s current breadth of capabilities but also to provide headroom for services yet to come: “What we’re striving for is becoming the operating system for your workday,” says CFO Kelly Steckelberg. But it’s all dependent on customers having an open mind about what exactly Zoom is—and the company delivering additional products that are worthy of the foundation it’s built with videoconferencing.

“On the one hand, that’s the opportunity,” says Yuan. “On the other hand, that’s also the challenge we face.”

‘THERE ARE A LOT OF NEW SERVICES IN THE PIPELINE’

Now, there’s nothing radical about the idea of selling videoconferencing as part of a larger suite of services. Indeed, that’s how all of Zoom’s principal competitors market their wares. In the case of Microsoft Teams—a rival to both Zoom and Slack—that suite is Microsoft 365. With Google Meet, it’s Google Workspace. Many businesses already pay for one of these two productivity bundles, and might default to Teams or Meet over Zoom for that reason alone. That gives Zoom a powerful incentive to make clear that it isn’t a single-product company.

From Excel to Gmail, Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace offer plenty of general-purpose productivity tools that Zoom seems unlikely to take on with its own counterparts. But when I ask Yuan if there are product categories that he’d avoid as being outside Zoom’s wheelhouse, he doesn’t name any. Instead, he rattles off some of the diverse recent additions to the company’s lineup. Zoom Events is for large-scale virtual gatherings, from internal all-hands sessions to ticketed affairs open to the public. Zoom Contact Center is a customer service platform that does voice, chat, and text messaging as well as video. And Zoom IQ for Sales uses AI to assess salespeople’s interactions with customers. Stay tuned: “There are a lot of new services in the pipeline,” says Yuan.

Ultimately, argues Zoom Chief Product Officer Oded Gal, customers appreciate the company’s focus: “Communication is a core capability, and they want someone who is dedicated to it, who can really answer to their needs and not be distracted with, you know, everything for everyone.”

Zoom’s larger competitors have chipped away at the lead it built up in video collaboration by starting earlier and taking the category more seriously, and Yuan feels the pressure: “We have to work even harder to make sure we understand the customer pain points,” he says. But how the race translates into current market share is unclear. In April 2020, Zoom said that it had 300 million daily active users, then corrected the record by stating that it meant daily meeting “participants,” with any individual who attended more than one meeting counting multiple times. It hasn’t updated this figure since. Google hasn’t revealed anything about Meet’s user base since April 2020, when it said the service was growing by three million people a day. Only Microsoft has shared a hard number recently: 270 million monthly active Teams users as of January.

‘I PERSONALLY HAD ZOOM FATIGUE’

Even if Zoom weren’t eager to expand beyond its core video-meeting offering, staying pretty much the same in the years to come would not be a viable option. Though the product’s pervasiveness during pandemic times has provided a windfall of free publicity, it’s also turned it into the poster child for videoconferencing’s ills. Stress from overuse is endemic to the category, but nobody talks about Microsoft Teams fatigue. It’s Zoom that gets the blame.

Yuan doesn’t skirt around the fact that the time we’ve all spent staring into a webcam can be taxing. In the early days of COVID-19, he recalls, after doing 19 Zoom meetings in one day, “I personally had Zoom fatigue. Quickly, we all realized that’s not sustainable.” Today, he adds, he spends a fair amount of time on Zoom Team Chat rather than turning everything into a video meeting. (Among Zoom’s measures to prevent its employees from getting burned out on its own product: Wednesdays are no-internal-meetings days.)

As knowledge workers finally start to head back to the office in meaningful numbers, Zoom’s next task is to bridge new and old ways of collaboration. With Zoom Rooms—a rich set of tools for running meetings in real-world conference rooms and bringing in participants located elsewhere—the company would seem to be well-positioned for an era when teamwork gets more physical again. A Rooms feature called Smart Gallery intelligently divvies the video feed from a conference-room camera into individual windows for attendees at the table, so they don’t look that different from the folks dialing in from home offices. “It actually brings that democracy back again, even in a hybrid meeting,” says Gal.

Yuan emphasizes that widespread support for hybrid work as a concept doesn’t mean we know exactly where we’re headed. “If you ask any business ‘What’s your definition of hybrid work?’ it’s very different,” he says. “How many days is that optional, flexible, or mandatory? Policies are different and are evolving, and also the technology tools are very different.”

Beyond the hybrid age lies . . . well, maybe the metaverse, whatever it might turn out to be. Yuan appears game to see how it could disrupt Zoom in its current form: “I think that video calls and AR, VR, and the metaverse eventually will converge into one thing,” he predicts.

Actually, Zoom has been at work on proto-metaverse technologies for quite a while. Way back in 2017, it partnered with an AR startup called Meta—no, not that Meta—to enable Zoom meetings involving 3D holographic representations of participants. Last year, it announced a collaboration with Meta—yes, this time the company formerly known as Facebook—to let Quest headset users attend Zoom meetings from within Meta’s Horizon Workrooms VR interface. Introduced in April, Zoom’s Immersive View dispenses with the Brady Bunch-style grid of participants in favor of plunking people into virtual environments such as an auditorium or classroom. (It’s similar to Microsoft Teams’ Together Mode, which debuted first.) Zoom even lets you represent yourself in a meeting as an Animoji-esque animated animal avatar, a lighthearted feature that Yuan demoed for me by briefly morphing into a fox during our conversation.

Even if the details of where the metaverse might take Zoom remain to be seen, the company does have a guiding approach in mind. “Eric’s vision has always been to make a Zoom meeting better than an in-person meeting,” CFO Steckelberg told me when we talked via Zoom. “And in some ways, it already is. You can record this, you can do transcription, you can have translation, all things that we couldn’t do as easily if we were sitting in person together.” When the company considers what the metaverse might mean for its products, she says, the overarching question is, “How do you create an experience so that you and I really feel like we’re even closer together?”

Zoom’s association with the pandemic-induced videoconferencing boom can cloud the credit it deserves for doing many things right long before it was a household name. When the service appeared in 2013, video calling had been around for years—it’s just that most of what was out there was too cumbersome and flaky to have that much impact on work or culture. Zoom was more approachable and reliable than what came before (including the venerable Webex, where Yuan, Steckelberg, and Gal all once worked).

“I still remember that in the early days of Zoom, sometimes I’d look at a screen literally for one hour without doing anything, thinking about how to simplify the user interface,” says Yuan. “To add a feature is easy. But to simplify is so hard.” From hybrid-work refinements to metaverse transformations, what the company adds in the years ahead will matter—but preserving that simplicity is critical to keeping the Zoom of tomorrow feeling like Zoom.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Harry McCracken is the global technology editor for Fast Company, based in San Francisco. In past lives, he was editor at large for Time magazine, founder and editor of Technologizer, and editor of PC World.